100% renewables might be fantasy, but it's what Australia is signing up for

Earlier this week, the Institute for Sustainable Futures in Sydney released a report that told us not only is 100 per cent renewable energy by 2030 possible – the Australian Energy Market Operator had already told us that – but it would also likely save us money.

But if you thought that the prospect of one of the most exciting and dramatic industrial revolutions taking place over the next decade would draw some interest from mainstream media and the political class – what with an election date announced the same day – then you would have been disappointed.

Instead, the stories published on RenewEconomy and The Guardian drew the same, repetitive diatribe from climate deniers, the coal lobby, nuclear boosters and right wing ideologues.

It’s a “fantasy” they say. And they perpetuated the same sort of myths espoused this week by the Northern Territory Treasurer – that renewables cause cables to “melt, collide and fail”– and that they will bring an end to modern civilisation. These and others myths are expertly dissected by UNSW energy expert Mark Diesendorf in this article today.

True, there are some who believe that targets such as 100 per cent renewable energy in defined time frames are unhelpful because they are so absolute, and appear dogmatic and unrealistic.

And there is a huge question-mark whether Australia could, as the ISF study suggests, install 4,500MW of solar each year (that is nearly the sum total of its installation to date), and if technologies such as hydrogen (to create renewable fuels) and ocean energy and geothermal will be ready and economic within the proposed time frames.

Certainly, such targets could not be met under the current Coalition government, which flails even Labor’s proposal for 50 per cent renewable energy by 2030 as an irresponsible, economy-ending policy, and which wants to remove the grants-based funding so essential to the roll-out of new technologies.

It is also doubtful that such targets could be met in a relatively small energy system dominated by a cabal of powerful incumbents and who appear to have the key regulators at their beck and call. They can’t stop new technology, but with changes to rules and tariffs, they can slow it down.

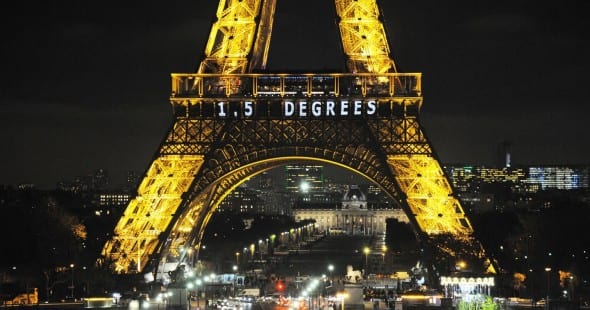

But if the Australian government looks carefully at the Paris climate agreement it is about to sign in New York, then it will realise that it has effectively signed up for a target in the same ball-park as that envisaged by ISF, and more or less spelt out in the Greens’ energy policy. It may not be 100 per cent renewables by 2030, but it will not be far short.

Rapid de-carbonisation and net zero emissions are the calling cards of this agreement – and recent soaring temperatures, record low ice levels in the Arctic and the devastating bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef only put more urgency to the targets.

The Coalition, though, is pretending otherwise. As environment minister Greg Hunt prepared to fly to New York, to join 168 countries gathered to sign the treaty, and with the promise of ratifying it later this year, he once again hailed Australia’s modest emissions reduction target – 26-28 per cent reductions by 2030 – as a great gift to the world.

This, of course, is a nonsense. Any number of institutions have pointed out that if Australia’s efforts were reciprocated across the world, we would be heading for global warming closer to 4°C than the aspirational 1.5°C included in the Paris agreement.

Hunt, on ABC TV’s Lateline program, said that Australia is doing more than any other country on “per capita” reductions. But that is because it has done so little in the past 20 years. As The Climate Institute pointed out, if Australia meets its 2030 targets – and it still has no policy to do that – only Saudi Arabia will have higher per capita emissions.

This may explain why it seems that Australia has not been invited to the so called “High Ambition Coalition” meeting that is being held in the lead-up to the signing of the Paris pact.

This group includes the Marshall Islands, the United States, European Union, Mexico, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, Norway, Brazil and a range of other developed and developing countries from around the world.

This group was instrumental in securing a more ambitious outcome in Paris by isolating countries, such as Saudi Arabia, that sought to weaken the outcome. The Australian government claimed membership of the group at the end of the Paris meeting but membership was always dependent on credentials.

So Hunt and his colleagues – including the tight cabal around prime minister Malcolm Turnbull who say the science is not settled (Senate leader George Brandis and National leaders Barnaby Joyce and Fiona Nash) should check the fine print.

The recent data – on emissions growth and average global warming – and the devastating impacts on the Great Barrier Reef highlights how little room there is to move.

The Paris agreement implies a strict carbon budget that may be exhausted by 2030. It does not allow for the increase in energy emissions Australia has posted since the carbon price was dumped, or the growth in overall emissions predicted by the government itself, or the building of new mega-mines in Queensland.

The Paris agreement calls for a rapid decarbonisation, and net zero emissions, and this was underlined by Christina Figueres, the secretary general of the UN climate body, the UNFCCC.

And in a direct contradiction of the Coalition’s standard position that “coal will cure poverty and hunger”, the UN said: “More carbon in the atmosphere equals more poverty.”

The Climate Institute said Australia will attend the event with domestic policies that are delivering rising pollution, sluggish clean energy investment and no plan for net zero emissions.

“Australia urgently needs a plan to build an economy shifting towards net zero emissions,” CEO John Connor said. “That plan needs to replace coal burning power stations with clean energy over the next 20 years, as well as maximise opportunities in the growing global clean energy economy.”

That’s 20 years, or by 2036. In the end, it doesn’t matter much if 100 per cent renewables is ever reached at all, much less at a particular date. But a rapid decarbonisation means high penetration renewables, rapid phasing out of coal, and investment in “enabling technologies” such as battery storage.

As Stanford University’s Tony Seba has suggested, the rapid fall in technology costs – principally solar and battery storage and smart technologies – will make oil, coal and even gas all but redundant within 15 years.

Whether that happens or not in a short time-frame is largely dependent on the attitude and business models of the incumbents. The power of the incumbents, and the influence of the fossil fuel and nuclear lobbies, and the right wing ideologues amongst them, is a major barrier. As the head of the China grid told the Big Oil lobby in Texas last month, it’s a matter of culture and attitude. They are harder nuts to crack than the technology.

MORE NEWS

OSW Gratefully Recognised as AlphaESS' Premium Distribution Partner in Australia

OSW Gratefully Recognised as AlphaESS' Premium Distribution Partner in Australia  We take great pride in commemorating our decade-long partnership with GoodWe

We take great pride in commemorating our decade-long partnership with GoodWe Anson Zhang CEO and Founder of OSW receiving the Hall of Fame Award from Smart Energy Council

Anson Zhang CEO and Founder of OSW receiving the Hall of Fame Award from Smart Energy Council All Energy 2023 Recap: OSW's Solar Innovations And Key Collaborations

All Energy 2023 Recap: OSW's Solar Innovations And Key Collaborations Supercharge Your Solar Business with Our Exclusive "Power Up with LONGi" Campaign

Supercharge Your Solar Business with Our Exclusive "Power Up with LONGi" Campaign